As Seventh-day Adventists, you should know that every facet of the 2,300 evening-morning prophecy has been challenged. One of the strongest challenges we face is proving the starting point for the Daniel 8:14 prophecy.

In our previous study, we learned that the 70-weeks were cut off from the 2,300 years, revealing to us that both prophecies have the same starting point. According to Daniel 9:25, the starting point for the 70-weeks prophecy was "from the going forth of the commandment to restore and to build Jerusalem." As students of prophecy, we know that all the commands that refer to reviving Jerusalem are found in the Book of Ezra (and one "decree" in Nehemiah), thus we need to examine that book to determine where that command resides.

However, a careful examination of this book reveals that there is a significant chronological issue in the pages of this historical account. I also believe that this chronological issue is one of the reasons we struggle to determine which command in Ezra was to "restore and build Jerusalem." In this study, we will carefully examine this issue and propose a correction that I believe may shed new light on the command to restore and build Jerusalem, which marks the beginning of the 2300 days.

The Chronology of the Persian Kings

Before solving the issue, we must clearly identify the sequence of kings who ruled Persia during and after the exile:

- Cyrus the Great

- Cambyses II

- Bardia (the False Smerdis)

- Darius I (the Great)

- Ahasuerus (Xerxes I) – husband of Queen Esther

- Artaxerxes I – the king who issued the 457 BC decree

With this order in mind, we can now examine Ezra’s account and see where the problem arises.

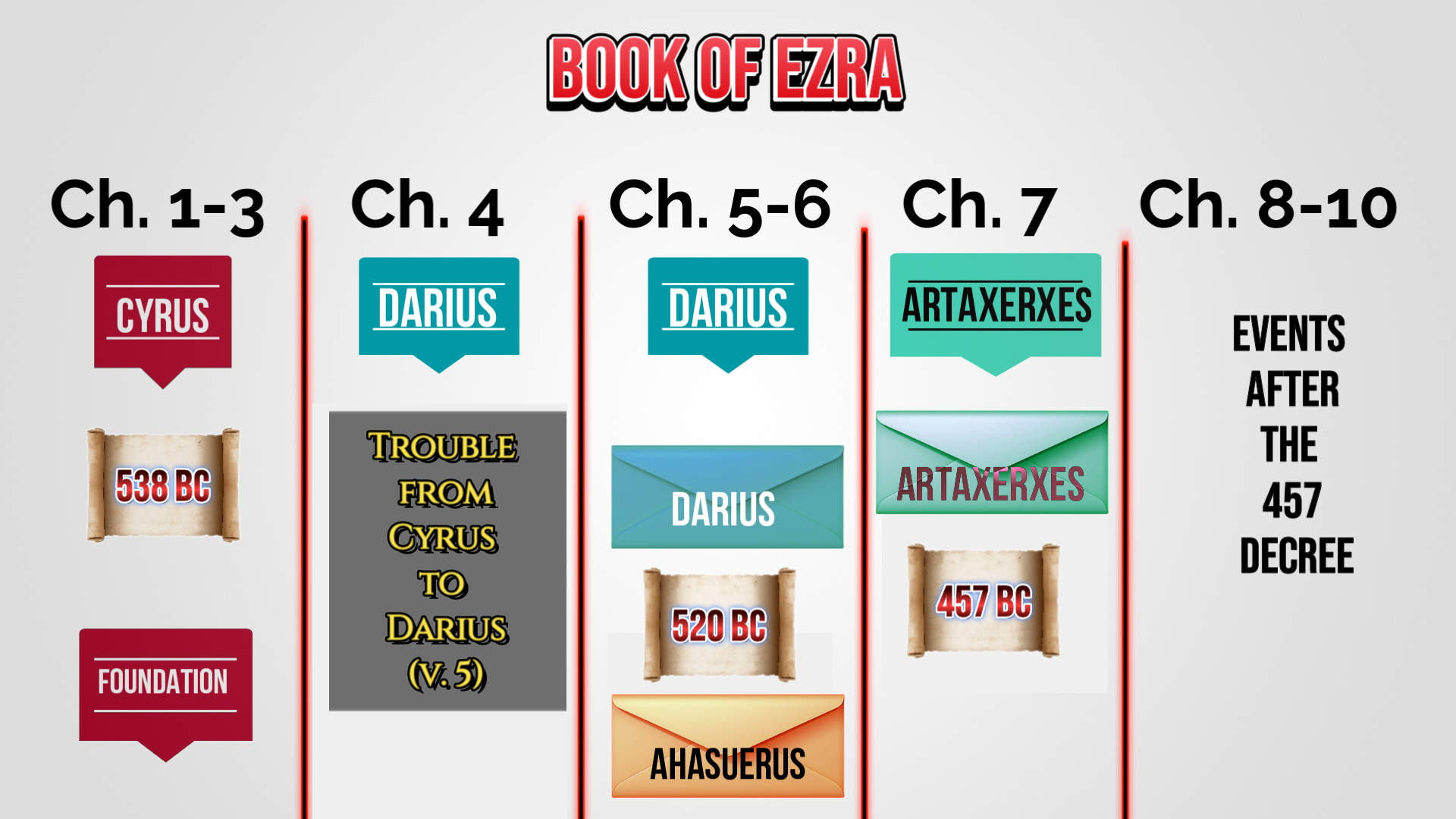

The Book of Ezra and Its Timeline

- Ezra 1–3: During the reign of Cyrus, the decree was issued to rebuild the temple in Jerusalem. The foundation is laid, and the people rejoice (Ezra 3:11).

- Ezra 4: The narrative suddenly shifts — jumping from Cyrus to Darius, and then oddly to Ahasuerus and Artaxerxes, before returning again to Darius in chapters 5–6.

This back-and-forth sequence seems inconsistent. Ezra 4 begins with opposition during the reigns of Cyrus and Darius:

And hired counsellors against them, to frustrate their purpose, all the days of Cyrus king of Persia, even until the reign of Darius king of Persia. Ezra 4:5

So chapter 4 begins by pointing out that the Children of Israel experienced problems from the surrounding nations as they tried to prohibit them from building the temple. And according to verse 5, these problems lasted from the reign of Cyrus to the reign of Darius.

However, right after this narrative of the trouble the Israelites had during these reigns, the chapter then refers to letters their adversaries wrote to Ahasuerus and Artaxerxes, kings who ruled after Darius. Notice what the text says:

And in the reign of Ahasuerus, in the beginning of his reign, wrote they unto him an accusation against the inhabitants of Judah and Jerusalem. Ezra 4:6

And in the days of Artaxerxes wrote Bishlam, Mithredath, Tabeel, and the rest of their companions, unto Artaxerxes king of Persia; and the writing of the letter was written in the Syrian tongue, and interpreted in the Syrian tongue. Ezra 4:7

The chapter begins with the context of issues between Darius and Cyrus, but the problem is that nothing in the chapter refers to those problems. As a matter of fact, most of the chapter is about the problems they faced under Artaxerxes. To add more complexity to this narrative, Ezra then closes the chapter with these words:

Then ceased the work of the house of God which is at Jerusalem. So it ceased unto the second year of the reign of Darius king of Persia. Ezra 4:24

Hopefully, you can see that, although the chapter's focus is on Ahasuerus and Artaxerxes, Ezra concludes his letter as if everything described in it occurred during Darius’ reign— a reign that occurred long before Ahasuerus and Artaxerxes ascended the throne. This is the historical issue that is at the heart of this article.

The Modern Scholar's explanation of the chronology problem

Most modern scholars explain the apparent chronological issue by suggesting that Ezra simply inserted a parenthetical section — a “look ahead” — showing that opposition to God’s people continued even under later kings.

While this explanation sounds logical, Ezra 4:24 disputes this theory. Had Ezra ended the chapter referring to Ahasuerus and Artaxerxes, then the modern scholar would be justified in their assertion. However, verse 24 disqualifies this view as currently constructed. Thus, the “look-ahead” explanation doesn’t fit the text’s own closing statement.

The legacy scholar's explanation of the chronology problem

Early Protestant commentators — such as Ellicott, Barnes, and the Pulpit Commentary — recognized the chronological problems in Ezra 4 and proposed a different theory. Although Ezra 4 names “Ahasuerus” and “Artaxerxes” in Ezra 4:6–7, these names actually refer to the two kings who ruled between Darius and Cyrus. In other words:

- Ahasuerus = Cambyses II

- Artaxerxes = The False Smerdis

This interpretation was even supported by Ellen G. White in her book, Prophets and Kings:

During the reign of Cambyses the work on the temple progressed slowly. And during the reign of the false Smerdis (called Artaxerxes in Ezra 4:7) the Samaritans induced the unscrupulous impostor to issue a decree forbidding the Jews to rebuild their temple and city. (p. 572)

A Different explanation

Although I truly believe that Ellen White was an inspired Messenger to the Seventh-day Adventist church, I believe that she simply went with the view of Ezra 4 that was commonly believed by most Protestants in her day. However, while that traditional explanation has long been accepted, it raises a serious question:

Would Ezra — a careful scribe and historian — have confused the names of Persian kings?

It seems unlikely that he would use the names Ahasuerus and Artaxerxes (the very kings who reigned after Darius) to refer to earlier monarchs. Ezra’s training and precision as a scribe make such a mistake improbable.

After deep study and prayer, I have concluded that the problem lies not with Ezra, but likely with how the book was later compiled. Thus, I came to the only logical conclusion—the references to Ahasuerus and Artaxerxes in Ezra 4 do not belong in the chapter.

A Logical Rearrangement of Ezra’s Chronology

Here’s the only logical conclusion for Ezra's discrepancy:

The references to the letters sent to Ahasuerus and Artaxerxes (Ezra 4:6–23) were likely inserted out of place by later compilers or copyists. If the reference to those letters is removed, the narrative flows smoothly and chronologically:

- Chapters 1–3: Cyrus issues his decree; the temple foundation is laid.

- Chapter 4: Opposition arises during Cyrus’ reign and continues through Darius' reign.

- Chapter 5: Adversaries write a letter to Darius (not Ahasuerus or Artaxerxes).

- Chapter 6: Darius confirms Cyrus’ decree; the temple is completed.

In this manner, everything from Ezra 1–6 would correctly belong entirely to the period of Cyrus and Darius, without interruption from later reigns.

Where does Ezra 4:6-23 belong?

If the letters to Ahasuerus and Artaxerxes don’t belong in Ezra 4, where do they fit?

Chronologically, they fit after chapter 6 — after the temple was completed, but before the 457 BC decree in Ezra 7.

This means that in the early years of Artaxerxes’s reign (before 457 BC), enemies of the Jews once again wrote to the king, warning that Jerusalem was being rebuilt. In response, Artaxerxes issued a decree to halt construction — a decree he later reversed in the seventh year of his reign (457 BC), when he authorized the restoration and rebuilding of Jerusalem (Ezra 7). This corrected sequence explains why Artaxerxes had to issue a second decree: his earlier one had stopped the work.

Why This Matters

This chronological correction not only resolves the internal inconsistencies in the book of Ezra — it also strengthens the prophetic timeline. Now, with these corrections, we can see that each monarch's reign is located within its proper timeline, and the historical account logically flows (see below).

Conclusion

When we allow Scripture and history to harmonize, the message becomes clear. The chronological issue in Ezra does not weaken our understanding — it enriches it. It shows that God’s word remains consistent, even when human records need correction.

As we continue our study, we’ll explore how this corrected chronology helps us better understand the decree to restore and build Jerusalem, and how it anchors the prophetic timeline of Daniel 8:14.

If you would like to see how the rearrangement of the Book of Ezra looks with the chronological corrections, you are welcome to download the PDF below.